Originally published in South Asian Voices

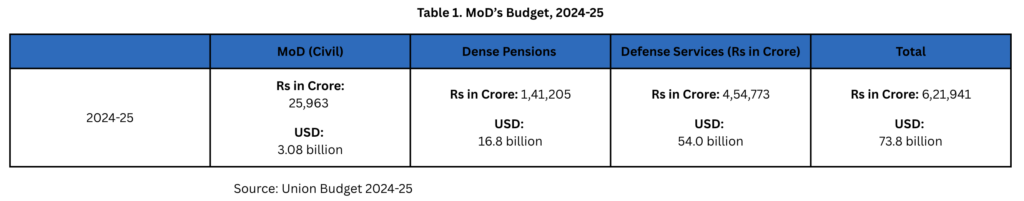

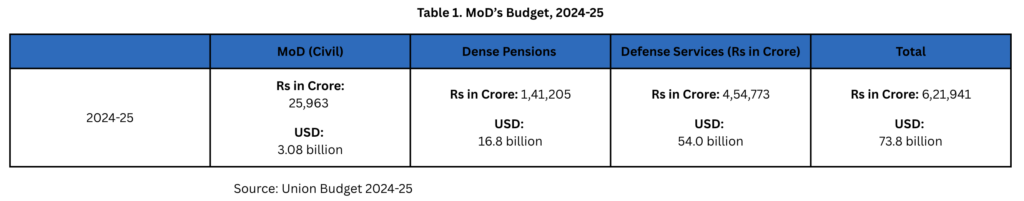

Last month, India and China reached an agreement to disengage from their military standoff on the Line of Actual Control in eastern Ladakh and conduct coordinated patrols along friction points. Despite this disengagement, however, India needs to invest in its comprehensive national power and defense preparedness to deal with the long-term threat from Beijing’s military modernization and regional influence. Presenting the Modi 3.0 government’s first budget in July 2024, Indian Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman allocated approximately USD $74 billion to the Ministry of Defense (MoD) (see Table 1). This allocation was a marginal increase of nearly USD $48 million over the amount allocated in the February 2024 Interim Budget. While the allocation does have the potential of having a positive bearing on India’s defense indigenization and domestic arms manufacturing, the rest of the picture appears quite mixed. Coming amidst a rapidly deteriorating global security environment, a volatile neighborhood, and the long-term threat from China, this allocation evokes serious questions regarding the adequacy of India’s defense preparedness.

By the Numbers

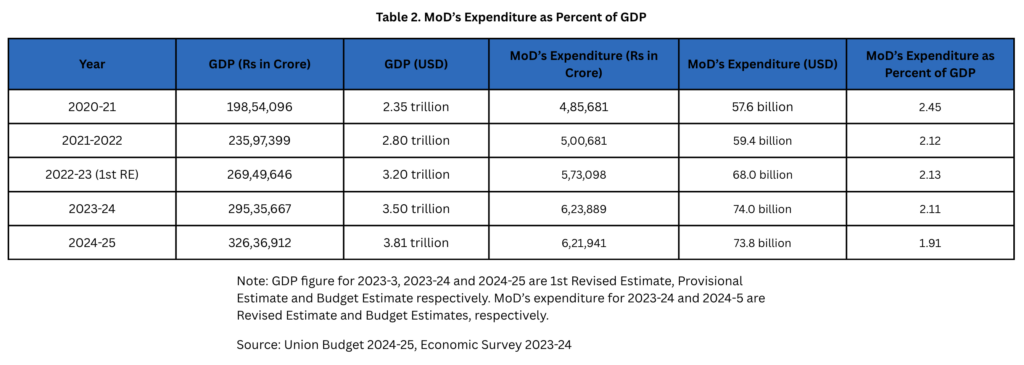

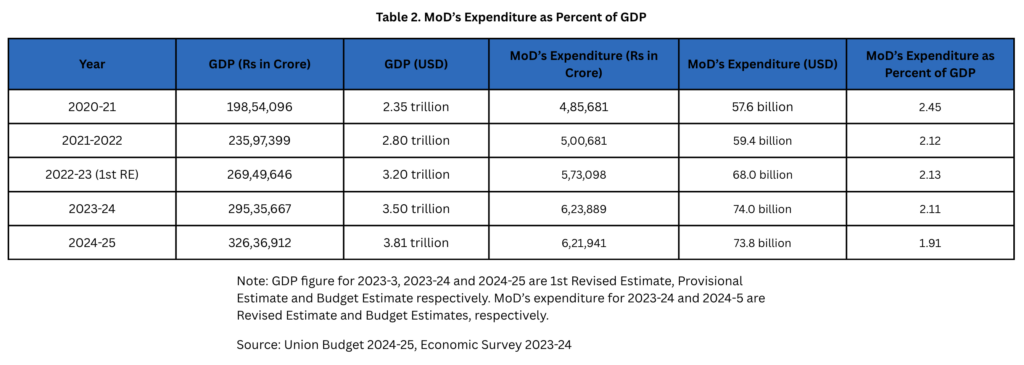

MoD’s latest allocation, which is a modest hike of 4.8 percent over the previous year’s allocation, remains the highest among all of India’s central government ministries. However, in terms of its share in the country’s wealth and union government outlays, the 2024-2025 defense budget is on slippery ground. Being just 1.91 percent of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) (see Table 2) and less than 13 percent of the overall budget, MoD’s latest budget is much lower than the 3 percent of GDP mark— as has been demanded in some quarters—and is a marked decline from the high mark of 18 percent of central government expenditure in 2016-17.

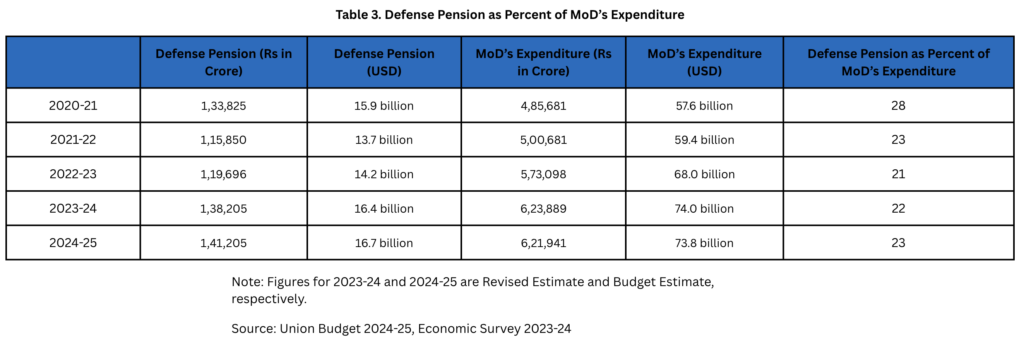

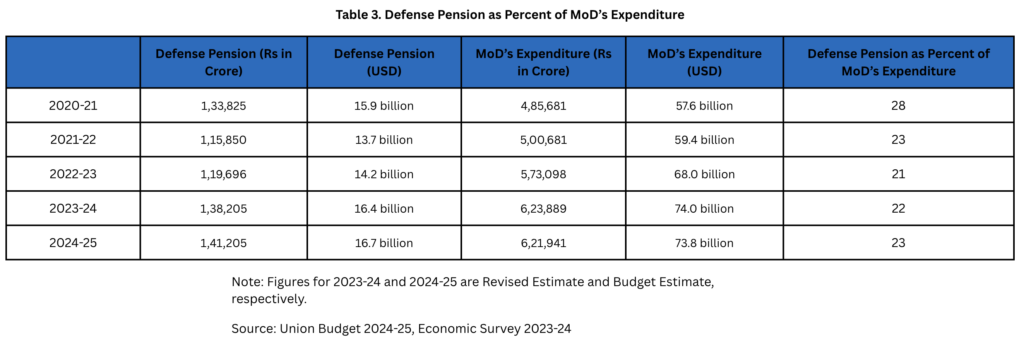

To further compound the problem of a relatively small budget, India’s defense expenditure has historically been dominated by manpower costs (see Table 3), leaving a meager share for capital expenditure, the bulk of which is meant for weapons procurement to ensure technological edge over India’s adversaries. The share of the budget allocated to procurement has been declining over the years largely due to rising personnel costs. Today, salaries and pensions make up more than half the budget (53 percent). Pensions alone account for 23 percent of the budget, compared to the 22 percent allocated to the procurement budget.

Winner: Indigenous Defense Industry

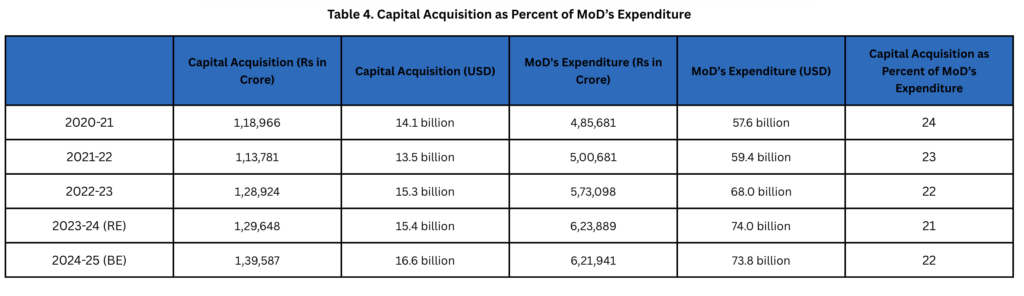

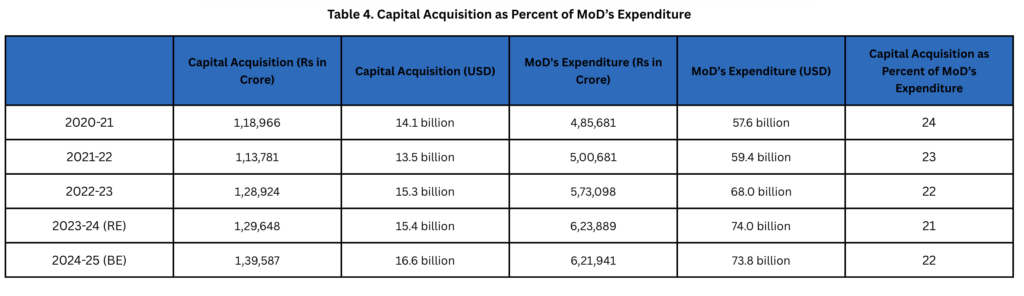

A notable feature of this defense budget is the continued emphasis on domestic defense technology and efforts towards building an indigenous industrial base. To promote local sourcing of arms and other supplies, the MoD has earmarked 75 percent of its total acquisition budget for procurement from domestic industry—up from 58 percent in 2020-21 (see Table 4). The enhanced allocation for domestic procurement will be a big boost for the domestic defense industry, which is poised to benefit from a host of other measures that the Modi government has announced as part of the Make in India and Atmanirbhar Bharat programs to improve India’s economic self-reliance. Some of the measures that complement the enhanced domestic procurement budget include the over 500 defense items reserved for manufacturing in India by the Department of Military Affairs and a domestic-industry-friendly procurement manual that was last revised in the form of the Defence Acquisition Procedure 2020.

To enhance the technological capacity of the domestic industry, especially the private sector, the budget has also made several notable provisions. For instance, the entire additional allocation of USD $48 million over and above the interim allocation is meant for the iDEX program, a flagship initiative run by the MoD’s Department of Defence Production to promote innovation within the domestic industry, especially small and marginal enterprises, start-ups, and individual innovators. With the scheme resulting in over 350 contracts since its launch in 2018 and the government approving successful iDEX projects worth USD $273 million for procurement, the additional allocation is not only an indicator of the scheme’s success, but will go a long way in fostering innovation within the Indian defense industrial ecosystem.

India needs to invest in its comprehensive national power and defense preparedness to deal with the long-term threat from Beijing’s military modernization and regional influence.

The Indian defense industry is also likely to gain from the announcement of a venture capital fund of USD $119 million to finance the country’s space economy, which the government estimates will expand by five times in the coming decade. The establishment of a corpus of USD $11 billion—announced in the Interim Budget and reiterated in Sitharaman’s July budget as part of government’s effort to encourage private industry to scale up research and innovation in the so-called “sunrise domains” is also likely to benefit the players in the defense industry.

Loser: DRDO

Interestingly, while the budget has made several announcements to give a fillip to the private sector and enhance its research and development (R&D) capacity, there is little for the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO), the premier defense R&D agency under the MoD. Compared to the USD $61 million earmarked for iDEX, the Technology Development Fund (TDF), a scheme run by the DRDO to foster innovation within the industry, has been allocated a paltry USD $7.1 million – an indication of the government’s dissatisfaction with the progress of the fund. This is particularly worrisome given that the fund is intended to finance relatively larger value innovation projects of importance to both DRDO and the armed forces.

DRDO’s resource constraints are also visible from its new budget, which is just 2.5 percent higher than its previous year’s allocation. Furthermore, its share among the defense services—which also includes the three armed forces and the erstwhile ordnance factories—has declined to 5.2 percent in the latest budget, from an all-time high of 6.7 percent in 2000-01.

DRDO’s declining share is a matter of concern for India’s defense innovation and self-reliance drive. Despite concerns of delays and cost overruns with its projects, the organization still remains India’s most significant R&D agency with technology interests spanning across both strategic and conventional weapons systems. It is also central to India’s larger defense innovation ecosystem, including big private companies, which depend on the DRDO’s resources and expertise to flourish. With the government announcing that it has earmarked 25 percent of R&D budget for industry, startups and academia, DRDO’s own projects, which are often inadequately funded, are likely to face further resource crunch going forward.

Mixed Progress in Defense Preparedness

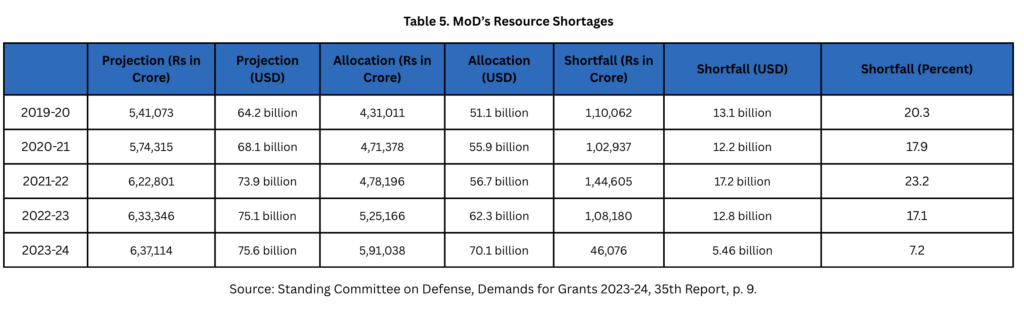

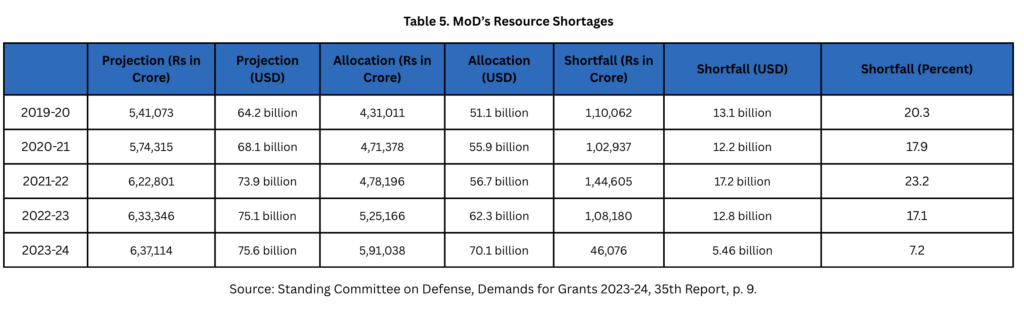

The modest increase in defense allocations year-on-year and the low share allocated to procurement in the budget are key factors behind the slow modernization of the Indian Armed Forces and the ever-widening resource gap with China, considered by many as India’s biggest strategic rival. The magnitude of the problem can be gauged from the fact that in 2022-23, nearly 50 percent of the USD $12.8 billion total shortage that the MoD faced was on account of paucity of funds to procure arms and other capital items for the Indian Armed Forces (see Table 5). The latest procurement budget, which is just 12 percent or USD $1.8 billion higher than the amount allocated for 2022-23, is inadequate to meet the resource gap, to say the least.

Notwithstanding the resource shortages, this defense budget does indicate some desire from the central government to improve the border infrastructure along the India-China border, which has been witnessing increasing Chinese aggression in recent years. The capital expenditure for the Border Roads Organization (BRO), the agency responsible for constructing India’s strategic roads, has been hiked by 30 percent. Some of the BRO’s capital allocation is meant for the development of strategic infrastructure along the Line of Actual Control, such as the Nyoma airfield in Ladakh, the Shinku La Tunnel in Himachal Pradesh, and the Nechiphu tunnel in Arunachal Pradesh, among others.

Coming amidst a rapidly deteriorating global security environment, a volatile neighborhood, and the long-term threat from China, this [marginal increase in defense] allocation evokes serious questions regarding the adequacy of India’s defense preparedness.

Squaring the Circle

In view of the worsening global security environment, the below five percent increase in India’s 2024-2025 defense budget is inadequate. This is doubly so when there is a big void in the procurement budget, which is critical for securing India’s technological parity with its adversaries. Given that the accrual of defense capability has a long-gestation period that requires a heavy and continuous investment, India needs a double-digit increase in defense allocation for a sustained period of at least 10 years or so. Although this is easier said than done in view of the scarcity of resources and competing demands from various socioeconomic sectors, India can hardly afford a modest annual spending growth that leaves a huge void in its defense modernization process. From a pure economic standpoint, India has the fiscal space to step up defense spending in a staggering manner to reach 2.5 percent of GDP in the next five years or so. While doing so, the government also needs to walk the talk on its self-reliance drive. While iDEX and other innovation measures are a great enabler, MoD must consider allocating higher resources, particularly to DRDO, which remains critical to India’s defense technological progress.

All calculations are the author’s own. The rate of conversion from INR to USD is as of November 26, 2024.

Originally published in South Asian Voices

Last month, India and China reached an agreement to disengage from their military standoff on the Line of Actual Control in eastern Ladakh and conduct coordinated patrols along friction points. Despite this disengagement, however, India needs to invest in its comprehensive national power and defense preparedness to deal with the long-term threat from Beijing’s military modernization and regional influence. Presenting the Modi 3.0 government’s first budget in July 2024, Indian Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman allocated approximately USD $74 billion to the Ministry of Defense (MoD) (see Table 1). This allocation was a marginal increase of nearly USD $48 million over the amount allocated in the February 2024 Interim Budget. While the allocation does have the potential of having a positive bearing on India’s defense indigenization and domestic arms manufacturing, the rest of the picture appears quite mixed. Coming amidst a rapidly deteriorating global security environment, a volatile neighborhood, and the long-term threat from China, this allocation evokes serious questions regarding the adequacy of India’s defense preparedness.

By the Numbers

MoD’s latest allocation, which is a modest hike of 4.8 percent over the previous year’s allocation, remains the highest among all of India’s central government ministries. However, in terms of its share in the country’s wealth and union government outlays, the 2024-2025 defense budget is on slippery ground. Being just 1.91 percent of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) (see Table 2) and less than 13 percent of the overall budget, MoD’s latest budget is much lower than the 3 percent of GDP mark— as has been demanded in some quarters—and is a marked decline from the high mark of 18 percent of central government expenditure in 2016-17.

To further compound the problem of a relatively small budget, India’s defense expenditure has historically been dominated by manpower costs (see Table 3), leaving a meager share for capital expenditure, the bulk of which is meant for weapons procurement to ensure technological edge over India’s adversaries. The share of the budget allocated to procurement has been declining over the years largely due to rising personnel costs. Today, salaries and pensions make up more than half the budget (53 percent). Pensions alone account for 23 percent of the budget, compared to the 22 percent allocated to the procurement budget.

Winner: Indigenous Defense Industry

A notable feature of this defense budget is the continued emphasis on domestic defense technology and efforts towards building an indigenous industrial base. To promote local sourcing of arms and other supplies, the MoD has earmarked 75 percent of its total acquisition budget for procurement from domestic industry—up from 58 percent in 2020-21 (see Table 4). The enhanced allocation for domestic procurement will be a big boost for the domestic defense industry, which is poised to benefit from a host of other measures that the Modi government has announced as part of the Make in India and Atmanirbhar Bharat programs to improve India’s economic self-reliance. Some of the measures that complement the enhanced domestic procurement budget include the over 500 defense items reserved for manufacturing in India by the Department of Military Affairs and a domestic-industry-friendly procurement manual that was last revised in the form of the Defence Acquisition Procedure 2020.

To enhance the technological capacity of the domestic industry, especially the private sector, the budget has also made several notable provisions. For instance, the entire additional allocation of USD $48 million over and above the interim allocation is meant for the iDEX program, a flagship initiative run by the MoD’s Department of Defence Production to promote innovation within the domestic industry, especially small and marginal enterprises, start-ups, and individual innovators. With the scheme resulting in over 350 contracts since its launch in 2018 and the government approving successful iDEX projects worth USD $273 million for procurement, the additional allocation is not only an indicator of the scheme’s success, but will go a long way in fostering innovation within the Indian defense industrial ecosystem.

India needs to invest in its comprehensive national power and defense preparedness to deal with the long-term threat from Beijing’s military modernization and regional influence.

The Indian defense industry is also likely to gain from the announcement of a venture capital fund of USD $119 million to finance the country’s space economy, which the government estimates will expand by five times in the coming decade. The establishment of a corpus of USD $11 billion—announced in the Interim Budget and reiterated in Sitharaman’s July budget as part of government’s effort to encourage private industry to scale up research and innovation in the so-called “sunrise domains” is also likely to benefit the players in the defense industry.

Loser: DRDO

Interestingly, while the budget has made several announcements to give a fillip to the private sector and enhance its research and development (R&D) capacity, there is little for the Defence Research and Development Organization (DRDO), the premier defense R&D agency under the MoD. Compared to the USD $61 million earmarked for iDEX, the Technology Development Fund (TDF), a scheme run by the DRDO to foster innovation within the industry, has been allocated a paltry USD $7.1 million – an indication of the government’s dissatisfaction with the progress of the fund. This is particularly worrisome given that the fund is intended to finance relatively larger value innovation projects of importance to both DRDO and the armed forces.

DRDO’s resource constraints are also visible from its new budget, which is just 2.5 percent higher than its previous year’s allocation. Furthermore, its share among the defense services—which also includes the three armed forces and the erstwhile ordnance factories—has declined to 5.2 percent in the latest budget, from an all-time high of 6.7 percent in 2000-01.

DRDO’s declining share is a matter of concern for India’s defense innovation and self-reliance drive. Despite concerns of delays and cost overruns with its projects, the organization still remains India’s most significant R&D agency with technology interests spanning across both strategic and conventional weapons systems. It is also central to India’s larger defense innovation ecosystem, including big private companies, which depend on the DRDO’s resources and expertise to flourish. With the government announcing that it has earmarked 25 percent of R&D budget for industry, startups and academia, DRDO’s own projects, which are often inadequately funded, are likely to face further resource crunch going forward.

Mixed Progress in Defense Preparedness

The modest increase in defense allocations year-on-year and the low share allocated to procurement in the budget are key factors behind the slow modernization of the Indian Armed Forces and the ever-widening resource gap with China, considered by many as India’s biggest strategic rival. The magnitude of the problem can be gauged from the fact that in 2022-23, nearly 50 percent of the USD $12.8 billion total shortage that the MoD faced was on account of paucity of funds to procure arms and other capital items for the Indian Armed Forces (see Table 5). The latest procurement budget, which is just 12 percent or USD $1.8 billion higher than the amount allocated for 2022-23, is inadequate to meet the resource gap, to say the least.

Notwithstanding the resource shortages, this defense budget does indicate some desire from the central government to improve the border infrastructure along the India-China border, which has been witnessing increasing Chinese aggression in recent years. The capital expenditure for the Border Roads Organization (BRO), the agency responsible for constructing India’s strategic roads, has been hiked by 30 percent. Some of the BRO’s capital allocation is meant for the development of strategic infrastructure along the Line of Actual Control, such as the Nyoma airfield in Ladakh, the Shinku La Tunnel in Himachal Pradesh, and the Nechiphu tunnel in Arunachal Pradesh, among others.

Coming amidst a rapidly deteriorating global security environment, a volatile neighborhood, and the long-term threat from China, this [marginal increase in defense] allocation evokes serious questions regarding the adequacy of India’s defense preparedness.

Squaring the Circle

In view of the worsening global security environment, the below five percent increase in India’s 2024-2025 defense budget is inadequate. This is doubly so when there is a big void in the procurement budget, which is critical for securing India’s technological parity with its adversaries. Given that the accrual of defense capability has a long-gestation period that requires a heavy and continuous investment, India needs a double-digit increase in defense allocation for a sustained period of at least 10 years or so. Although this is easier said than done in view of the scarcity of resources and competing demands from various socioeconomic sectors, India can hardly afford a modest annual spending growth that leaves a huge void in its defense modernization process. From a pure economic standpoint, India has the fiscal space to step up defense spending in a staggering manner to reach 2.5 percent of GDP in the next five years or so. While doing so, the government also needs to walk the talk on its self-reliance drive. While iDEX and other innovation measures are a great enabler, MoD must consider allocating higher resources, particularly to DRDO, which remains critical to India’s defense technological progress.

All calculations are the author’s own. The rate of conversion from INR to USD is as of November 26, 2024.