China’s economic engagement with the Taliban has often been a subject of scrutiny, with many believing China would play a major economic role in Afghanistan after the U.S. withdrawal from the country in 2021. Data from the over three and a half years since the Taliban came to power, however, show that China has not eagerly stepped into such a role. China’s imports from Afghanistan have fallen more often than they have risen and Chinese investment stock has remained below levels seen around a decade ago. Facing limited agreements and stalling projects, the Taliban has started to look elsewhere for economic support.

Many believed China would be quick to assume an economic role in Afghanistan when a former PLA senior colonel argued China could step into the void as the United States withdrew in 2021. After the Taliban took over, the group called China their “most important partner” and said they would rely on Chinese funds to rebuild Afghanistan. However, in the three and a half years since the takeover, China’s imports from Afghanistan have declined more often than they have grown and investment has remained flat at lower levels than those seen in 2012–2014. Few new projects have been fully committed to ink. Against Afghanistan’s complicated backdrop of internal divisions and continuing attacks from terrorist and resistance groups, among other factors, China’s government will continue to proceed with caution in expanding economic ties, forcing the Taliban to consider other options for economic support.

The Bilateral Trade Imbalance Grows

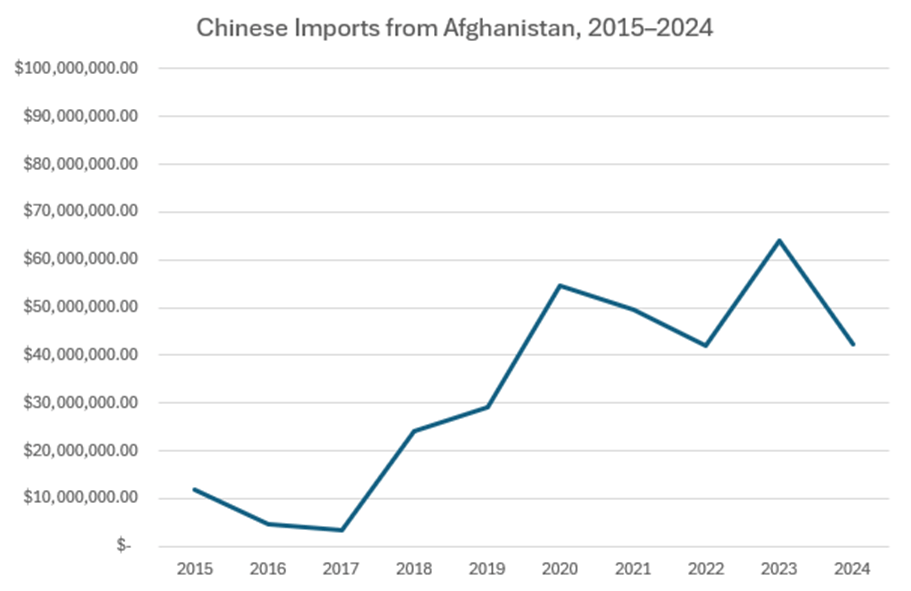

Data from General Administration of Customs China (GACC) show China’s total trade with Afghanistan sharply increased after the Taliban takeover following a period of decline.

Yet this increase was unbalanced, as China’s exports more than doubled from 2021–2024 while imports fell more than they grew in the same period. Afghanistan’s trade deficit with China was decreasing prior to the Taliban takeover but saw increases each year after 2021, more than tripling from 2021–2024.

China’s imports from Afghanistan fell in 2021, 2022, and 2024 after three years of year-on-year growth from 2018–2020, seeing only a brief increase in 2023 when pine nut imports from Afghanistan spiked temporarily. The Taliban’s concern for its growing trade imbalance with China led the group to push to establish a bilateral working group on the issue in March 2025.

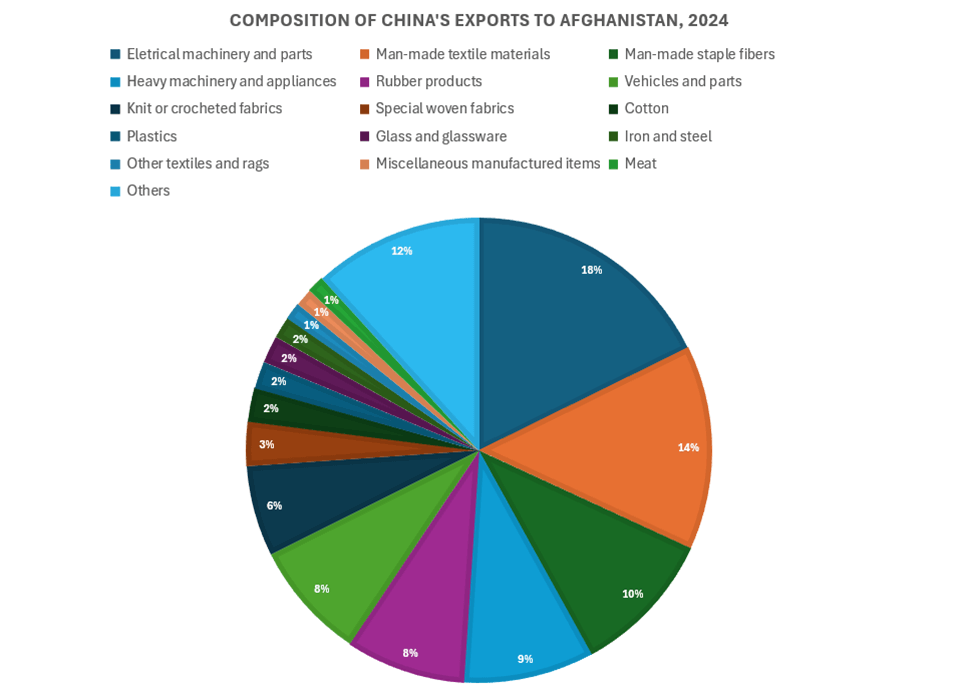

China’s exports to Afghanistan are very diverse, with electrical and heavy machinery and various textiles making up the largest shares.

At the same time, China imports pine nuts from Afghanistan but little else. Resource extraction investments had little effect on the composition of China’s imports from Afghanistan; GACC data show China imported no precious or semiprecious metals nor oil products from the country in 2024. For critical minerals, only imports of zinc increased from zero in 2020 to around $1.3 million in 2024.

Even China’s pine nut imports from Afghanistan, as part of the Pine Nut Air Corridor initiative, have fluctuated since the takeover after a sharp rise in 2019 and 2020. These imports fell year-on-year in 2021, 2022, and 2024; relative to 2020, 2024 imports were down over $15 million, which amounts to 34% of China’s total imports from Afghanistan in 2024.

Flattened Investment

China has maintained roughly the same level of investment stock in Afghanistan since the takeover, with 2021 and 2023 figures matching 2020 figures and only a short-lived $12 million increase in 2022 after three years of modest year-on-year increases from 2018–2020. Current investment stock levels are still down from those seen in 2012–2014. Reports indicate China has fully inked only a handful of new investment deals since the takeover, including:

- A $310–350 million investment for gold mining in Takhar,

- 3 additional mining deals of unknown amounts,

- Roughly $13.1 million to expand pine nut processing, and

- A cement factory agreement for $145 million over 30 years.

Despite dozens of media reports of Chinese investors pledging investments in Afghanistan, most remain unsigned. Most notable is a reported offer to invest $10 billion in Afghanistan’s lithium sector made by “Gochin company” which Chinese battery producer Gotion Energy denies refers to Gotion. The Taliban did not accept that offer, and their hesitation is understandable; on existing projects, China has continued to make limited progress.

For example, many headlines noted an investment by a subsidiary of Chinese national oil giant CNPC in Afghanistan’s Amu Darya oil fields but the project is not new; it apparently constitutes projects CNPC previously held the contract for. While the project reportedly sold 130,000 tons of crude in June 2024 and received promised equipment deliveries that December, it also reportedly fell short of the promised 2023 investment target of $150 million, which a Taliban official previously warned could end the agreement. This would not be the first time the project fell short; CNPC’s earlier project was scrapped in 2018 by the former Afghan government over a lack of progress. The Taliban’s 2024 calls to expedite progress demonstrate continuing frustration.

A further struggling project is the Mes Aynak copper mine, which was awarded to a Chinese company in 2008 and is still not extracting copper. After 16 years of delays and months of Taliban pressure, the Chinese company finally started new construction in July 2024, but only for a basic access road. In October 2024, Taliban officials stressed the need to launch full operations, highlighting perceptions of limited progress.

The slow advancement of these projects poses challenges for initiatives like the Wakhan Corridor, the narrow stretch of northeastern Afghanistan connecting the country to China. Taliban officials privately hope for Chinese investment to open the Wakhan Corridor but this has not been granted, limiting the initiative’s prospects.

The Taliban Turns Elsewhere

China’s economic engagement with the Taliban after the U.S. withdrawal has been less than enthusiastic. Trade is more unbalanced, investment remains limited, and existing projects still struggle. As China avoids fully stepping into the void in Afghanistan, the Taliban is pursuing other options for economic engagement, most recently the UAE and—perhaps most notably—India. Afghan media recently listed India as one of Afghanistan’s biggest trading partners after Iran and Pakistan, not mentioning China. Taliban engagement with India has concerned Chinese analysts who fear U.S.-India coordination on Afghanistan could threaten China’s BRI interests. China will have to charter a path between its stated interests in Afghanistan and lukewarm engagement before the Taliban turns elsewhere for support.

China’s economic engagement with the Taliban has often been a subject of scrutiny, with many believing China would play a major economic role in Afghanistan after the U.S. withdrawal from the country in 2021. Data from the over three and a half years since the Taliban came to power, however, show that China has not eagerly stepped into such a role. China’s imports from Afghanistan have fallen more often than they have risen and Chinese investment stock has remained below levels seen around a decade ago. Facing limited agreements and stalling projects, the Taliban has started to look elsewhere for economic support.

Many believed China would be quick to assume an economic role in Afghanistan when a former PLA senior colonel argued China could step into the void as the United States withdrew in 2021. After the Taliban took over, the group called China their “most important partner” and said they would rely on Chinese funds to rebuild Afghanistan. However, in the three and a half years since the takeover, China’s imports from Afghanistan have declined more often than they have grown and investment has remained flat at lower levels than those seen in 2012–2014. Few new projects have been fully committed to ink. Against Afghanistan’s complicated backdrop of internal divisions and continuing attacks from terrorist and resistance groups, among other factors, China’s government will continue to proceed with caution in expanding economic ties, forcing the Taliban to consider other options for economic support.

RelatedPost

The Bilateral Trade Imbalance Grows

Data from General Administration of Customs China (GACC) show China’s total trade with Afghanistan sharply increased after the Taliban takeover following a period of decline.

Yet this increase was unbalanced, as China’s exports more than doubled from 2021–2024 while imports fell more than they grew in the same period. Afghanistan’s trade deficit with China was decreasing prior to the Taliban takeover but saw increases each year after 2021, more than tripling from 2021–2024.

China’s imports from Afghanistan fell in 2021, 2022, and 2024 after three years of year-on-year growth from 2018–2020, seeing only a brief increase in 2023 when pine nut imports from Afghanistan spiked temporarily. The Taliban’s concern for its growing trade imbalance with China led the group to push to establish a bilateral working group on the issue in March 2025.

China’s exports to Afghanistan are very diverse, with electrical and heavy machinery and various textiles making up the largest shares.

At the same time, China imports pine nuts from Afghanistan but little else. Resource extraction investments had little effect on the composition of China’s imports from Afghanistan; GACC data show China imported no precious or semiprecious metals nor oil products from the country in 2024. For critical minerals, only imports of zinc increased from zero in 2020 to around $1.3 million in 2024.

Even China’s pine nut imports from Afghanistan, as part of the Pine Nut Air Corridor initiative, have fluctuated since the takeover after a sharp rise in 2019 and 2020. These imports fell year-on-year in 2021, 2022, and 2024; relative to 2020, 2024 imports were down over $15 million, which amounts to 34% of China’s total imports from Afghanistan in 2024.

Flattened Investment

China has maintained roughly the same level of investment stock in Afghanistan since the takeover, with 2021 and 2023 figures matching 2020 figures and only a short-lived $12 million increase in 2022 after three years of modest year-on-year increases from 2018–2020. Current investment stock levels are still down from those seen in 2012–2014. Reports indicate China has fully inked only a handful of new investment deals since the takeover, including:

- A $310–350 million investment for gold mining in Takhar,

- 3 additional mining deals of unknown amounts,

- Roughly $13.1 million to expand pine nut processing, and

- A cement factory agreement for $145 million over 30 years.

Despite dozens of media reports of Chinese investors pledging investments in Afghanistan, most remain unsigned. Most notable is a reported offer to invest $10 billion in Afghanistan’s lithium sector made by “Gochin company” which Chinese battery producer Gotion Energy denies refers to Gotion. The Taliban did not accept that offer, and their hesitation is understandable; on existing projects, China has continued to make limited progress.

For example, many headlines noted an investment by a subsidiary of Chinese national oil giant CNPC in Afghanistan’s Amu Darya oil fields but the project is not new; it apparently constitutes projects CNPC previously held the contract for. While the project reportedly sold 130,000 tons of crude in June 2024 and received promised equipment deliveries that December, it also reportedly fell short of the promised 2023 investment target of $150 million, which a Taliban official previously warned could end the agreement. This would not be the first time the project fell short; CNPC’s earlier project was scrapped in 2018 by the former Afghan government over a lack of progress. The Taliban’s 2024 calls to expedite progress demonstrate continuing frustration.

A further struggling project is the Mes Aynak copper mine, which was awarded to a Chinese company in 2008 and is still not extracting copper. After 16 years of delays and months of Taliban pressure, the Chinese company finally started new construction in July 2024, but only for a basic access road. In October 2024, Taliban officials stressed the need to launch full operations, highlighting perceptions of limited progress.

The slow advancement of these projects poses challenges for initiatives like the Wakhan Corridor, the narrow stretch of northeastern Afghanistan connecting the country to China. Taliban officials privately hope for Chinese investment to open the Wakhan Corridor but this has not been granted, limiting the initiative’s prospects.

The Taliban Turns Elsewhere

China’s economic engagement with the Taliban after the U.S. withdrawal has been less than enthusiastic. Trade is more unbalanced, investment remains limited, and existing projects still struggle. As China avoids fully stepping into the void in Afghanistan, the Taliban is pursuing other options for economic engagement, most recently the UAE and—perhaps most notably—India. Afghan media recently listed India as one of Afghanistan’s biggest trading partners after Iran and Pakistan, not mentioning China. Taliban engagement with India has concerned Chinese analysts who fear U.S.-India coordination on Afghanistan could threaten China’s BRI interests. China will have to charter a path between its stated interests in Afghanistan and lukewarm engagement before the Taliban turns elsewhere for support.