Editor’s Note: The authors are seasoned experts on Turkish foreign policy and have published extensively on Turkey’s evolving regional role.

Prof. Meliha Altunışık is a faculty member in the Department of International Relations at Middle East Technical University (METU) in Ankara whose research focuses primarily on the international relations of the Middle East and Turkish foreign policy. Some of her recent publications include: “The trajectory of a modified middle power: an attempt to make sense of Turkey’s foreign policy in its centennial,” Turkish Studies, 2023; “Humanitarian diplomacy as Turkey’s national role conception and performance: evidence from Somalia and Afghanistan,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 2023; “Turkey’s foreign policy toward Israel: co-existing of ideology and pragmatism in the age of global and regional shifts”, Int Polit, 2025; “A New Project of a Gulf-Based Regional Order in the Middle East?” Middle East Journal, forthcoming.

Dr. Derya Göçer is a faculty member at the Graduate School of Social Sciences at Middle East Technical University, where she also serves as Chair of the Middle East Studies Program and of the Area Studies Program. She holds a Ph.D. in International Relations from the London School of Economics. Her research focuses on Turkey’s evolving relations with the Middle East, particularly Iran and the Gulf, as well as broader regional dynamics such as security, state transformation, and the international impact of the Belt and Road Initiative. Dr. Göçer has published extensively on regional politics with a focus on Turkey’s engagement with China. Her work has been published by centers such as Carnegie Endowment and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. She also teaches and writes on social movements in the Middle East. Her work combines international relations theory, area studies, and historical sociology to explore the international embeddedness of political change in the region.

By Barbara Slavin, Distinguished Fellow, Middle East Perspectives

As the Middle East continues to face instability from heightened military conflicts and shifting regional dynamics, Turkey’s approach towards Iraq has evolved in significant ways. Since 2020, Turkey has actively sought normalization with the central government in Baghdad to augment its longstanding engagement with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Turkey’s Iraq policy has traditionally focused on maintaining Iraq’s territorial integrity and addressing perceived security threats posed by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which Turkey regards as a terrorist group. Ankara’s strategy in Iraq is shaped by domestic politics, including its long conflict with Turkey’s Kurdish minority, Iraq’s internal instability and power struggles, and regional geopolitical dynamics, particularly Iran’s influence in Iraq and the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria. Ultimately, Turkey’s Iraq policy remains guided primarily by security considerations, reflecting both domestic imperatives and regional strategic considerations.

Relations with the KRG’s leading political party, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), remain robust, overcoming tensions that followed a 2017 referendum on independence for the region, which failed to achieve its goals. Turkey’s relationship with the KDP’s rival, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) are more challenging due to Turkey’s perception that the PUK under Bafel Talabani’s leadership continues to tolerate activities by the PKK.

The call from the long-jailed leader of the PKK Abdullah Öcalan on February 27, 2025 for “disarmament and dissolution” of his organization opened the way for a new context not only in domestic politics but also regionally. In response, the PKK announced a “ceasefire” on March 3. There remain challenges, but if the process is successful, it has the potential to transform Turkey-Iraq relations.

Simultaneously, Turkey has strengthened security ties with Baghdad through intelligence-sharing agreements and coordinated military actions. High-level security meetings in August 2023 and March 2024 led to key agreements, including a Memorandum of Understanding on Military and Security Cooperation. Under this memorandum, Iraq designated the PKK as a “banned organization,” aligning with Turkey’s counterterrorism narrative. Iraq reaffirmed this stance during a visit to Baghdad in April 2024 by Turkish President Recep Tayyib Erdoğan, his first in 13 years. Iraq also agreed to turn a Turkish base in Bashiqa, established in northern Iraq ostensibly to fight ISIS, into a Turkey-Iraq Joint Training and Cooperation Center, although this has not yet occurred.

Turkish diplomatic activity has markedly intensified, as evidenced by frequent meetings between Turkish officials and Iraqi counterparts, including Sunni Muslim leaders Mohamed al-Halbousi, a former speaker of the Iraqi parliament, and Ammar al-Hakim, the former leader of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, an important Shi’ite organization.

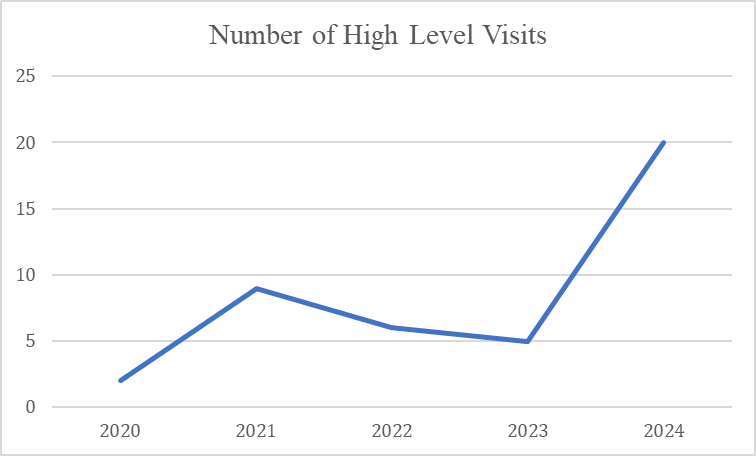

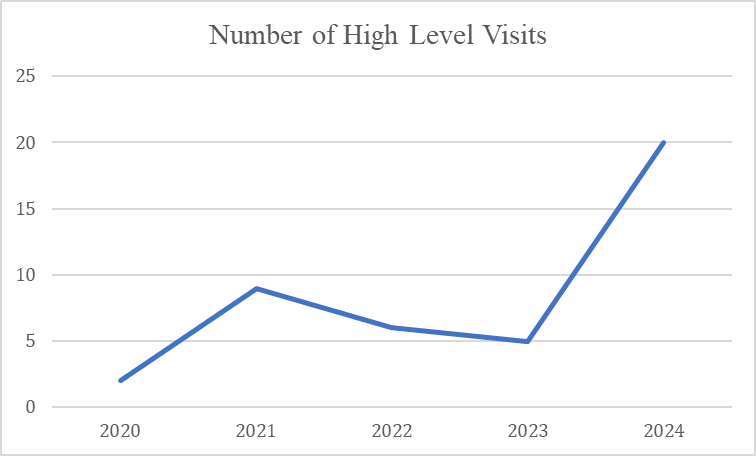

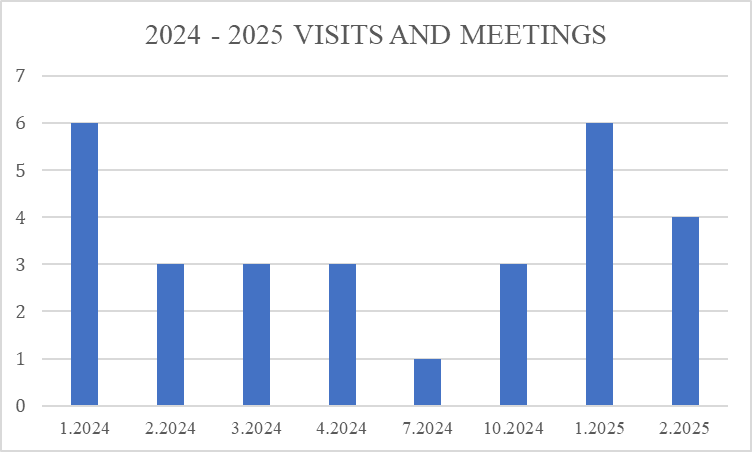

Figure 1: High-Level Visits, Including Turkey’s President, Ministers, and the Head of MIT

Figure 1, based on data compiled from various official Turkish sources, highlights the growing diplomatic engagement between Turkey and Iraq, encompassing both the central government and the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG).

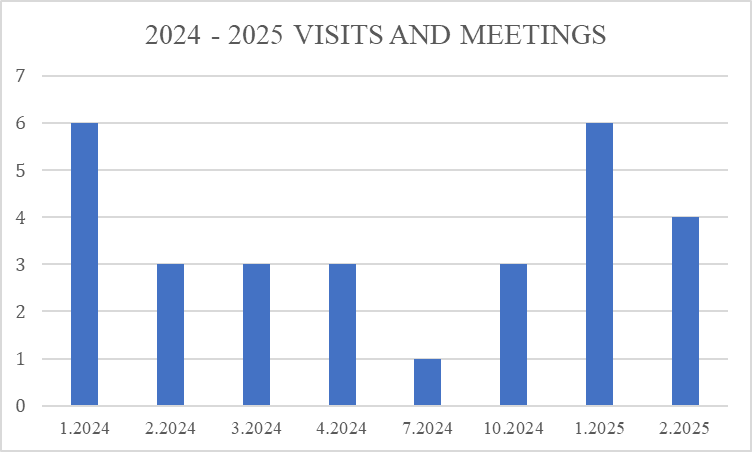

Figure 2: 2024-2025

Our fieldwork underscores Turkey’s aim to institutionalize diplomatic relations and transcend leader-driven relationships to cushion against future political uncertainties in Iraq. Pressure from the Trump administration on Iraq to reduce its dependence on Iran offers Turkey a wider strategic window to deepen engagement.

Military Dimension of Turkey’s Policy

Turkish military operations in Iraq go back to the 1980s as Turkey sought to dismantle the PKK infrastructure. In 2023, a significant increase in operations occurred, concentrating on the regions of Metina, Zap, and Avaşin.

Baghdad criticized Turkish operations and the establishment and expansion of military bases in Iraq as a violation of its sovereignty. Iran-backed militia groups, including Kata’ib Hezbollah, targeted Turkish bases. Ankara’s recent agreement to transfer control of the Bashiqa base to Iraq illustrates its intent to mitigate sovereignty concerns and institutionalize bilateral security cooperation.

Over the past year, Turkey also escalated military actions against PKK figures in the PUK-controlled Sulaymaniyah region and warned PUK leader Talabani to sever ties with the group or face consequences. In 2023, Turkey banned flights to Sulaymaniyah as a pressure tactic. Internal divisions within the PUK have weakened Talabani’s position, with factions led by Lahur and Qubad Talabani advocating closer ties with Turkey and the KRG. Turkey’s long-term strategy may involve leveraging such divisions to try to further isolate the PKK.

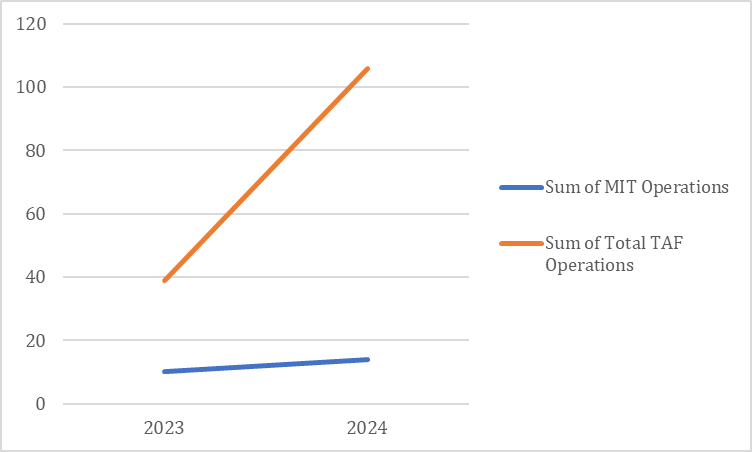

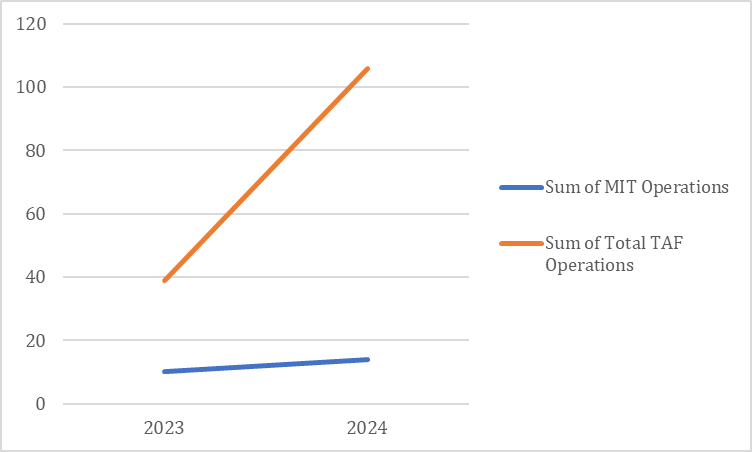

Figure 3: Increase in the number of TAF and MIT operations towards Syria and Iraq

Figure 4: Breakdown of TAF operations in Iraq

| Claw-1 | 2019 |

| Claw-2 | 2019 |

| Claw-3 | 2020 |

| Claw-Lightning | 2021 |

| Claw-Lock | 2022 |

| Claw-Tiger | 2023 |

Source: Data compiled from Ministry of Defense

Domestically, significant shifts surrounding Turkey’s Kurdish policy have emerged. The call by Öcalan for the PKK to disband aligns strategically with regional dynamics, particularly the weakened PKK position resulting from intensive Turkish military operations. Turkey’s deepening cooperation with both Baghdad and the KRG has further restricted the PKK’s maneuverability in the region.

Consequently, Turkey’s Kurdish policy is entering a new phase, characterized by enhanced dual-track coordination with Iraq and the KRG and the strategic use of military and diplomatic means. As Ankara navigates this complex geopolitical landscape, potential shifts in U.S. policy and Iran’s regional strategies will play critical roles in shaping the outcomes of Turkey’s engagements in Iraq and Syria. Moving forward, Turkey must carefully balance its counterterrorism objectives with broader regional dynamics to ensure the long-term stability of its southern borders.

Challenges to Turkey’s Strategy

Turkey’s strategy faces four critical challenges:

- Balancing Baghdad and Erbil: Tensions persist due to unresolved federal issues between the Iraqi government and the KRG, particularly regarding oil revenue and territorial administration. Ankara’s close relations with one party invariably impact its relations with the other, demanding careful diplomatic balancing.

- Intra-Kurdish Rivalries: Continued rivalry between the KDP and PUK complicates Turkey’s strategic objectives in northern Iraq, providing operational space for the PKK despite Turkish military pressure.

- Iraqi Internal Fragility: Iraq remains politically fragile (on alert category in the Fragile State Index), with elections scheduled for November 11 expected to reignite internal power struggles. These domestic uncertainties risk disrupting the current trajectory of Turkey-Iraq relations.

- Security Capacity Limitations: Iraq’s limited capacity to enforce security agreements is exemplified by difficulties implementing the Sinjar Agreement that was signed in 2020 between Erbil and Baghdad to stabilize the Yezidi majority area, which had been devastated by ISIS. Lack of capacity of Iraq’s armed forces was also a contributing factor in Turkey’s decision to resume military actions against the PKK.

Regional geopolitical tensions, particularly between the U.S. and Iran, also have implications for Turkey’s strategic calculus in Iraq. Iraq remains a geopolitical battleground despite attempts by the Iraqi leadership to achieve regional neutrality. Iran’s enduring influence in Iraqi politics, combined with Turkey’s burgeoning security ties, creates an inherent strategic competition, highlighting the vulnerability of Turkey’s gains in Iraq. Iranian influence is under serious challenge, due to Trump’s maximum pressure policy on Iran and Iraq’s increasing reluctance to associate with Iran in a regional context. But U.S. policy adds more uncertainty, particularly if the Trump administration carries out plans to withdraw forces from Syria.

Conclusion

Our research demonstrates that Turkish policy towards Iraq over the last five years has been dominated by a dual-track strategy. Turkey has added collaboration with Iraqi actors to its already considerable repertoire of engagements with the KRG and has invested in both diplomatic and military toolsets. This expansion has allowed Turkey to be more adept in times of rapid domestic and regional shifts. Yet, this approach has limitations. Turkey’s ability to sustain this strategy will depend on its capacity to navigate shifting regional alliances, manage internal political dynamics, and balance engagement in Iraq with broader geopolitical constraints.

The authors note that their work on Turkey-Iraq relations is a project of The Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) at the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) in Berlin, with funding by Stiftung Mercator and the German Federal Foreign Office.

Editor’s Note: The authors are seasoned experts on Turkish foreign policy and have published extensively on Turkey’s evolving regional role.

Prof. Meliha Altunışık is a faculty member in the Department of International Relations at Middle East Technical University (METU) in Ankara whose research focuses primarily on the international relations of the Middle East and Turkish foreign policy. Some of her recent publications include: “The trajectory of a modified middle power: an attempt to make sense of Turkey’s foreign policy in its centennial,” Turkish Studies, 2023; “Humanitarian diplomacy as Turkey’s national role conception and performance: evidence from Somalia and Afghanistan,” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 2023; “Turkey’s foreign policy toward Israel: co-existing of ideology and pragmatism in the age of global and regional shifts”, Int Polit, 2025; “A New Project of a Gulf-Based Regional Order in the Middle East?” Middle East Journal, forthcoming.

Dr. Derya Göçer is a faculty member at the Graduate School of Social Sciences at Middle East Technical University, where she also serves as Chair of the Middle East Studies Program and of the Area Studies Program. She holds a Ph.D. in International Relations from the London School of Economics. Her research focuses on Turkey’s evolving relations with the Middle East, particularly Iran and the Gulf, as well as broader regional dynamics such as security, state transformation, and the international impact of the Belt and Road Initiative. Dr. Göçer has published extensively on regional politics with a focus on Turkey’s engagement with China. Her work has been published by centers such as Carnegie Endowment and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. She also teaches and writes on social movements in the Middle East. Her work combines international relations theory, area studies, and historical sociology to explore the international embeddedness of political change in the region.

By Barbara Slavin, Distinguished Fellow, Middle East Perspectives

As the Middle East continues to face instability from heightened military conflicts and shifting regional dynamics, Turkey’s approach towards Iraq has evolved in significant ways. Since 2020, Turkey has actively sought normalization with the central government in Baghdad to augment its longstanding engagement with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Turkey’s Iraq policy has traditionally focused on maintaining Iraq’s territorial integrity and addressing perceived security threats posed by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which Turkey regards as a terrorist group. Ankara’s strategy in Iraq is shaped by domestic politics, including its long conflict with Turkey’s Kurdish minority, Iraq’s internal instability and power struggles, and regional geopolitical dynamics, particularly Iran’s influence in Iraq and the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria. Ultimately, Turkey’s Iraq policy remains guided primarily by security considerations, reflecting both domestic imperatives and regional strategic considerations.

Relations with the KRG’s leading political party, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), remain robust, overcoming tensions that followed a 2017 referendum on independence for the region, which failed to achieve its goals. Turkey’s relationship with the KDP’s rival, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) are more challenging due to Turkey’s perception that the PUK under Bafel Talabani’s leadership continues to tolerate activities by the PKK.

The call from the long-jailed leader of the PKK Abdullah Öcalan on February 27, 2025 for “disarmament and dissolution” of his organization opened the way for a new context not only in domestic politics but also regionally. In response, the PKK announced a “ceasefire” on March 3. There remain challenges, but if the process is successful, it has the potential to transform Turkey-Iraq relations.

Simultaneously, Turkey has strengthened security ties with Baghdad through intelligence-sharing agreements and coordinated military actions. High-level security meetings in August 2023 and March 2024 led to key agreements, including a Memorandum of Understanding on Military and Security Cooperation. Under this memorandum, Iraq designated the PKK as a “banned organization,” aligning with Turkey’s counterterrorism narrative. Iraq reaffirmed this stance during a visit to Baghdad in April 2024 by Turkish President Recep Tayyib Erdoğan, his first in 13 years. Iraq also agreed to turn a Turkish base in Bashiqa, established in northern Iraq ostensibly to fight ISIS, into a Turkey-Iraq Joint Training and Cooperation Center, although this has not yet occurred.

Turkish diplomatic activity has markedly intensified, as evidenced by frequent meetings between Turkish officials and Iraqi counterparts, including Sunni Muslim leaders Mohamed al-Halbousi, a former speaker of the Iraqi parliament, and Ammar al-Hakim, the former leader of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, an important Shi’ite organization.

Figure 1: High-Level Visits, Including Turkey’s President, Ministers, and the Head of MIT

Figure 1, based on data compiled from various official Turkish sources, highlights the growing diplomatic engagement between Turkey and Iraq, encompassing both the central government and the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG).

Figure 2: 2024-2025

Our fieldwork underscores Turkey’s aim to institutionalize diplomatic relations and transcend leader-driven relationships to cushion against future political uncertainties in Iraq. Pressure from the Trump administration on Iraq to reduce its dependence on Iran offers Turkey a wider strategic window to deepen engagement.

Military Dimension of Turkey’s Policy

Turkish military operations in Iraq go back to the 1980s as Turkey sought to dismantle the PKK infrastructure. In 2023, a significant increase in operations occurred, concentrating on the regions of Metina, Zap, and Avaşin.

Baghdad criticized Turkish operations and the establishment and expansion of military bases in Iraq as a violation of its sovereignty. Iran-backed militia groups, including Kata’ib Hezbollah, targeted Turkish bases. Ankara’s recent agreement to transfer control of the Bashiqa base to Iraq illustrates its intent to mitigate sovereignty concerns and institutionalize bilateral security cooperation.

Over the past year, Turkey also escalated military actions against PKK figures in the PUK-controlled Sulaymaniyah region and warned PUK leader Talabani to sever ties with the group or face consequences. In 2023, Turkey banned flights to Sulaymaniyah as a pressure tactic. Internal divisions within the PUK have weakened Talabani’s position, with factions led by Lahur and Qubad Talabani advocating closer ties with Turkey and the KRG. Turkey’s long-term strategy may involve leveraging such divisions to try to further isolate the PKK.

Figure 3: Increase in the number of TAF and MIT operations towards Syria and Iraq

Figure 4: Breakdown of TAF operations in Iraq

| Claw-1 | 2019 |

| Claw-2 | 2019 |

| Claw-3 | 2020 |

| Claw-Lightning | 2021 |

| Claw-Lock | 2022 |

| Claw-Tiger | 2023 |

Source: Data compiled from Ministry of Defense

Domestically, significant shifts surrounding Turkey’s Kurdish policy have emerged. The call by Öcalan for the PKK to disband aligns strategically with regional dynamics, particularly the weakened PKK position resulting from intensive Turkish military operations. Turkey’s deepening cooperation with both Baghdad and the KRG has further restricted the PKK’s maneuverability in the region.

Consequently, Turkey’s Kurdish policy is entering a new phase, characterized by enhanced dual-track coordination with Iraq and the KRG and the strategic use of military and diplomatic means. As Ankara navigates this complex geopolitical landscape, potential shifts in U.S. policy and Iran’s regional strategies will play critical roles in shaping the outcomes of Turkey’s engagements in Iraq and Syria. Moving forward, Turkey must carefully balance its counterterrorism objectives with broader regional dynamics to ensure the long-term stability of its southern borders.

Challenges to Turkey’s Strategy

Turkey’s strategy faces four critical challenges:

- Balancing Baghdad and Erbil: Tensions persist due to unresolved federal issues between the Iraqi government and the KRG, particularly regarding oil revenue and territorial administration. Ankara’s close relations with one party invariably impact its relations with the other, demanding careful diplomatic balancing.

- Intra-Kurdish Rivalries: Continued rivalry between the KDP and PUK complicates Turkey’s strategic objectives in northern Iraq, providing operational space for the PKK despite Turkish military pressure.

- Iraqi Internal Fragility: Iraq remains politically fragile (on alert category in the Fragile State Index), with elections scheduled for November 11 expected to reignite internal power struggles. These domestic uncertainties risk disrupting the current trajectory of Turkey-Iraq relations.

- Security Capacity Limitations: Iraq’s limited capacity to enforce security agreements is exemplified by difficulties implementing the Sinjar Agreement that was signed in 2020 between Erbil and Baghdad to stabilize the Yezidi majority area, which had been devastated by ISIS. Lack of capacity of Iraq’s armed forces was also a contributing factor in Turkey’s decision to resume military actions against the PKK.

Regional geopolitical tensions, particularly between the U.S. and Iran, also have implications for Turkey’s strategic calculus in Iraq. Iraq remains a geopolitical battleground despite attempts by the Iraqi leadership to achieve regional neutrality. Iran’s enduring influence in Iraqi politics, combined with Turkey’s burgeoning security ties, creates an inherent strategic competition, highlighting the vulnerability of Turkey’s gains in Iraq. Iranian influence is under serious challenge, due to Trump’s maximum pressure policy on Iran and Iraq’s increasing reluctance to associate with Iran in a regional context. But U.S. policy adds more uncertainty, particularly if the Trump administration carries out plans to withdraw forces from Syria.

Conclusion

Our research demonstrates that Turkish policy towards Iraq over the last five years has been dominated by a dual-track strategy. Turkey has added collaboration with Iraqi actors to its already considerable repertoire of engagements with the KRG and has invested in both diplomatic and military toolsets. This expansion has allowed Turkey to be more adept in times of rapid domestic and regional shifts. Yet, this approach has limitations. Turkey’s ability to sustain this strategy will depend on its capacity to navigate shifting regional alliances, manage internal political dynamics, and balance engagement in Iraq with broader geopolitical constraints.

The authors note that their work on Turkey-Iraq relations is a project of The Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) at the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) in Berlin, with funding by Stiftung Mercator and the German Federal Foreign Office.