A year and a half after a sweeping offensive, the Arakan Army is poised to seize control of Rakhine State from Myanmar’s military junta. Its rapid expansion has been enabled by its extensive network across the anti-junta movement. As the Arakan Army solidifies its influence in southwest Myanmar, it now holds the leverage and power to shape the trajectory of the country’s civil war.

Editor’s Note: Stimson’s Myanmar Project seeks a variety of analytical perspectives on issues relating to Myanmar’s civil war, domestic politics, foreign relations, and other topics. Drake Avila is an independent analyst who studies conflict dynamics in Myanmar and was previously a daily news briefing writer for Frontier Myanmar.

By Pamela Kennedy, Deputy Director, East Asia Program

Since launching its sweeping offensive in November 2023, the Arakan Army (AA) has positioned itself to seize its home state, Rakhine, from the Myanmar military. On the eastern fringe of the Bay of Bengal, Rakhine has made international headlines as the site of the 2017 Rohingya genocide and the host to major Indian and Chinese infrastructure projects. The impact of Rakhine’s fall for those issues has been well-explored elsewhere. Less examined is how AA allies in southwest Myanmar have mobilized to support their patron, the AA, and how the group could shape the wider conflict. Although the AA is an avowedly ethnonationalist rebel group primarily interested in self-determination for Rakhine, it has expressed solidarity with the broader anti-junta movement and built up an extensive network of allies within it.

The axis that has emerged as a result has enabled the AA to expand its influence close to India in Chin State, threaten the military’s industrial base in Magway and Bago regions, and endanger the junta’s grip on the rice bowl of Ayeyarwady Region. As of early 2025, the AA is now the premier benefactor of insurgent activity in the southwest, with at least 17 groups and likely far more that have fought alongside and in parallel to the AA in Rakhine, Chin, Bago, Magway, and Ayeyarwady. This has greatly threatened the junta, complicated the AA’s relationship with the National Unity Government (NUG), and further entrenched its place in Chin state. Through these alliances, the AA has the power to greatly impact the trajectory of Myanmar’s civil war.

The Role of AA Allies and Territorial Gains

Supporting ambushes and concurrent offensives conducted with allied groups demonstrated the reach of the AA’s network as the group besieged the military government’s Ann-based Western Regional Military Command (RMC) in Rakhine from October 7–December 20, 2024. These allies have since helped the AA fortify Rakhine’s borders and venture into neighboring areas in 2025. The AA’s focus is likely on disrupting the military’s ability to move along Rakhine’s borders, especially by severing its control of the Pathein-Monywa road in Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady.

A month after the AA’s siege of Ann began, the Chin Brotherhood—an alliance of defense forces primarily based in southern Chin state—initiated a supporting offensive in Chin’s Mindat and Falam towns. They ultimately captured Mindat in December 2024, thanking the AA for providing supplies, weapons, and reinforcements. Falam was captured in April 2025.

Along the Rakhine Yoma, the Rakhine mountain range, at least six resistance groups have supported AA operations from as early as August 2024 to March 2025. Before the fall of Ann, these resistance groups were mostly focused along the Ann-Padan road to Magway. Resistance allies have also since helped the AA advance into three neighboring regions: Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady. Ayeyarwady resistance fighters reportedly helped the AA in southern Rakhine and are likely assisting operations in their home region.

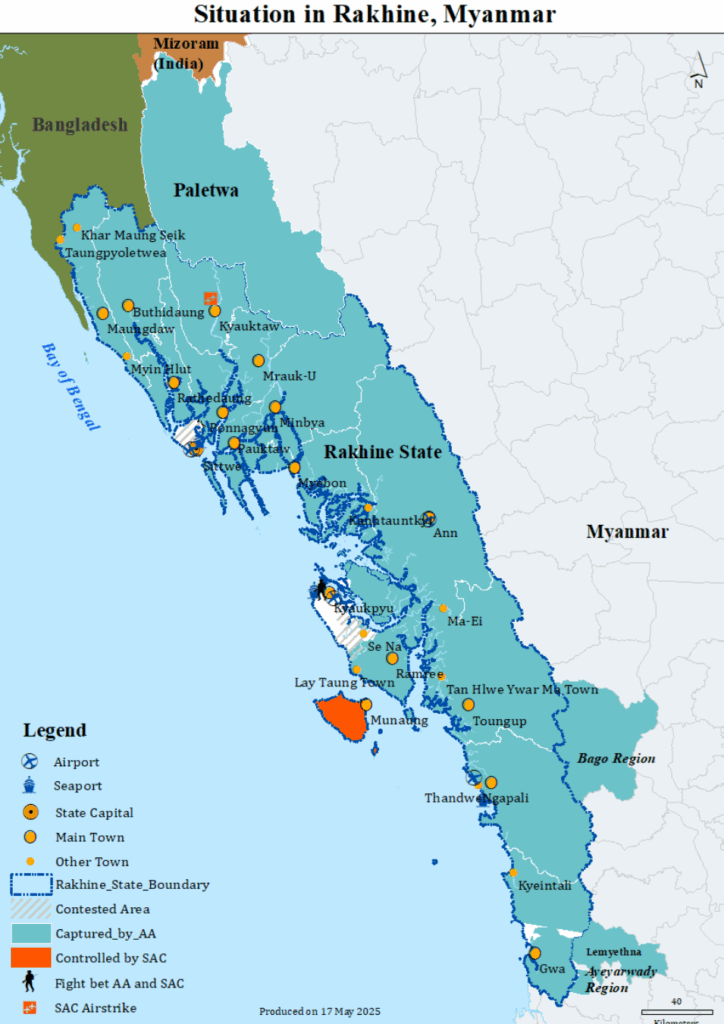

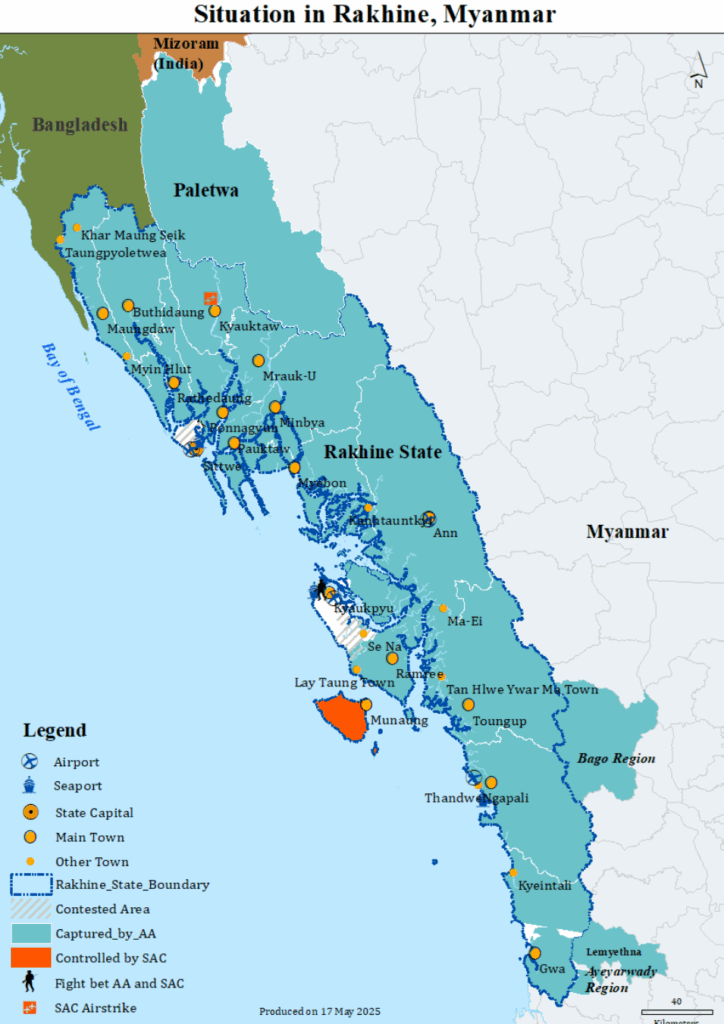

Map of AA territorial control courtesy of the United Nations Development Programme, Cox’s Bazaar Analysis and Research Unit, Weekly Media Monitoring, Year 7, Issue 19, May 11–17, 2025, page 4.

Paltry Peace Prospects as the AA’s Power Grows

As argued by the International Institute of Strategic Studies, powerful ethnic armies like the AA are in a deteriorating security dilemma with the Myanmar military. Failing to hold peripheries like Rakhine, the military conducts airstrikes and imposes blockades to disrupt rebel governance. Unable to prevent either, the AA launched ally-supported forays into neighboring states and regions to retaliate and secure its borders.

China has attempted to mediate these tensions, but Beijing has fewer pressure options for the AA than for armed groups based near China’s borders. Although the AA and the Myanmar military reportedly met for talks in China in December 2024, no agreement was apparently reached. The AA has avoided overly antagonizing China by withholding a full-scale assault on northern Kyaukphyu Township, the site of oil and gas terminals, a deep seaport, and other Chinese infrastructure projects. However, clashes continued near these projects in April 2025.

Although the earthquake that struck Myanmar on March 28, 2025, prompted announcements of unilateral ceasefires from the AA and the Myanmar military, the AA captured a military outpost a day after the announcement and the military has continued a brutal bombing campaign. This is unsurprising; in a February speech, Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing emphasized the growing threat of the AA and allied “terrorists” in Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady.

In Magway and Bago, the AA and its allies threaten most of the factories feeding the Myanmar military war machine. Although limited to the western edge of Ayeyarwady in April 2025, conflict between the AA and military could expand, threatening an estimated 30% of national rice production and further decreasing the number of townships where Min Aung Hlaing can hold his planned election. With increasing leverage, the AA has fewer reasons to engage in ceasefire negotiations.

Threats to Other Resistance Stakeholders

While the AA’s increasing leverage has put the junta on notice in western Myanmar, there are challenges for other resistance actors. Supporting other actors threatens the junta but has also enabled the AA to expand its influence in Chin State and in Bamar-majority areas that are considered the NUG’s home turf. This has exacerbated splits within the Chin resistance while potentially pulling resistance groups from the NUG’s orbit, further fracturing an already divided resistance movement and decreasing the NUG’s long-term viability as the default alternative to the military government.

Disagreements over post-coup governance undergirded by geographic and tribal differences solidified into two rival Chin resistance coalitions in late 2023: the Chinland Council and Chin Brotherhood. Although agreeing to merge as the Chin National Council in February 2025, they have yet to write a governing constitution, indicating full reconciliation will not be an immediate process. The Chinland Council is led by the oldest armed group in the state, the Chin National Army (CNA), which has been alarmed by AA support for the Chin Brotherhood. A CNA leader claimed “[t]he AA’s hidden political agenda is to create a greater Arakan State” and implied the Chin Brotherhood was helping this effort.

The CNA has been one of the NUG’s few official EAO allies, so AA activities in Chin could be a further stumbling block to cooperation with the NUG. The NUG has attempted to attract the AA to its umbrella, for example, by diluting a statement about alleged AA atrocities against the Rohingya in May 2024. However, NUG efforts have likely been constrained by the perception it is dominated by National League for Democracy members who supported the military’s anti-AA campaigns pre-coup. Further, the NLD had refused to engage with Rakhine nationalist parties when it unilaterally selected the state’s chief minister. Indicating strained relations at present, the NUG was not among about 30 groups that sent letters congratulating the AA on the 16th anniversary of its founding.

People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) under the NUG might opt for more closely following the AA because of the NUG’s challenges in funding, arming, and strategizing to suit smaller groups’ local conditions. Well-armed and geographically closer to smaller groups, the AA is likely eager to support localized movements rather than deal with the NUG and its national leadership aspirations.

Offering an attractive alternative to consolidated power under the NUG in Myanmar, the AA has attracted sympathetic groups like the Generation Z Youth Army (GZA) and the Burma National Revolutionary Army (BNRA), which have bad blood with the NUG: an NUG-aligned PDF detained several members of the GZA in 2023, and BNRA leader Bo Nagar frequently accuses the NUG of trying to undermine his group. The GZA and BNRA fought alongside the AA in the capture of Mindat, and the GZA fought under the AA in Rakhine in February 2024. Contrasting the AA’s success in countering the junta with the NUG’s own challenges, other sympathetic groups may find the AA a more attractive and effective alternative for countering the junta, further complicating a resolution to Myanmar’s civil war.

Conclusion

The AA is expanding its influence across southwestern Myanmar through an axis of post-coup resistance groups, broadening its alliance network across the country. The AA has long had a presence in northern, northeastern, and southeastern Myanmar, giving it multiple theaters in which to fight against the Myanmar military and shape national politics. Now, in the southwest, the AA will unequivocally be the senior patron with proteges to direct for its cause, and in the Bamar-majority heartland, no less.

The AA’s sphere of influence is not just prying the southwest away from the military orbit; it is also reordering resistance power politics altogether. The AA’s successes and increasing support from smaller actors demonstrate that the group is establishing a sphere of influence beyond Rakhine that threatens the junta and rivals the NUG.

Some observers believe the AA faces a dilemma of expanding beyond Rakhine State or seize towns like Sittwe and Kyaukphyu. Instead, the AA may consider the two towns more useful outside of their control. As long as they threaten the capital, Sittwe, and the center of Chinese projects, Kyaukphyu, the Myanmar military must divert resources away from more active fronts in Bago, Magway, and Ayeyarwady to avoid losing these critical sites in Rakhine.

The AA will likely continue to invest most heavily in Ayeyarwady. The Rakhine Yoma’s forbidding peaks fortify AA borders with Magway and Bago, but the Yoma slopes into more traversable foothills on the Ayeyarwady border, making this area the most likely route for a Myanmar military counteroffensive. Moreover, the Pathein-headquartered Southwestern RMC is just 40 miles from the border. To cut off the base from the north, the AA has staged a four-pronged attack roughly along the Pathein-Monywa road in Ayeyarwady. Next, they may seek to blockade the road connecting the RMC to the Hainggyikyun naval base to the south and disrupt lines of communication to the east. Just as local allies have been force-multipliers in other theaters, resistance groups in Ayeyarwady and allies will be key for navigating the terrain, justifying the group’s incursion as a liberation rather than an invasion, and attracting local recruits. The AA’s ability to leverage groups in this manner will continue to bolster its offensives, continuing to challenge the junta in western Myanmar in the coming months.

Drake Avila is an independent analyst who studies conflict dynamics in Myanmar and was previously a daily news briefing writer for Frontier Myanmar.

A year and a half after a sweeping offensive, the Arakan Army is poised to seize control of Rakhine State from Myanmar’s military junta. Its rapid expansion has been enabled by its extensive network across the anti-junta movement. As the Arakan Army solidifies its influence in southwest Myanmar, it now holds the leverage and power to shape the trajectory of the country’s civil war.

Editor’s Note: Stimson’s Myanmar Project seeks a variety of analytical perspectives on issues relating to Myanmar’s civil war, domestic politics, foreign relations, and other topics. Drake Avila is an independent analyst who studies conflict dynamics in Myanmar and was previously a daily news briefing writer for Frontier Myanmar.

By Pamela Kennedy, Deputy Director, East Asia Program

Since launching its sweeping offensive in November 2023, the Arakan Army (AA) has positioned itself to seize its home state, Rakhine, from the Myanmar military. On the eastern fringe of the Bay of Bengal, Rakhine has made international headlines as the site of the 2017 Rohingya genocide and the host to major Indian and Chinese infrastructure projects. The impact of Rakhine’s fall for those issues has been well-explored elsewhere. Less examined is how AA allies in southwest Myanmar have mobilized to support their patron, the AA, and how the group could shape the wider conflict. Although the AA is an avowedly ethnonationalist rebel group primarily interested in self-determination for Rakhine, it has expressed solidarity with the broader anti-junta movement and built up an extensive network of allies within it.

The axis that has emerged as a result has enabled the AA to expand its influence close to India in Chin State, threaten the military’s industrial base in Magway and Bago regions, and endanger the junta’s grip on the rice bowl of Ayeyarwady Region. As of early 2025, the AA is now the premier benefactor of insurgent activity in the southwest, with at least 17 groups and likely far more that have fought alongside and in parallel to the AA in Rakhine, Chin, Bago, Magway, and Ayeyarwady. This has greatly threatened the junta, complicated the AA’s relationship with the National Unity Government (NUG), and further entrenched its place in Chin state. Through these alliances, the AA has the power to greatly impact the trajectory of Myanmar’s civil war.

The Role of AA Allies and Territorial Gains

Supporting ambushes and concurrent offensives conducted with allied groups demonstrated the reach of the AA’s network as the group besieged the military government’s Ann-based Western Regional Military Command (RMC) in Rakhine from October 7–December 20, 2024. These allies have since helped the AA fortify Rakhine’s borders and venture into neighboring areas in 2025. The AA’s focus is likely on disrupting the military’s ability to move along Rakhine’s borders, especially by severing its control of the Pathein-Monywa road in Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady.

A month after the AA’s siege of Ann began, the Chin Brotherhood—an alliance of defense forces primarily based in southern Chin state—initiated a supporting offensive in Chin’s Mindat and Falam towns. They ultimately captured Mindat in December 2024, thanking the AA for providing supplies, weapons, and reinforcements. Falam was captured in April 2025.

Along the Rakhine Yoma, the Rakhine mountain range, at least six resistance groups have supported AA operations from as early as August 2024 to March 2025. Before the fall of Ann, these resistance groups were mostly focused along the Ann-Padan road to Magway. Resistance allies have also since helped the AA advance into three neighboring regions: Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady. Ayeyarwady resistance fighters reportedly helped the AA in southern Rakhine and are likely assisting operations in their home region.

Map of AA territorial control courtesy of the United Nations Development Programme, Cox’s Bazaar Analysis and Research Unit, Weekly Media Monitoring, Year 7, Issue 19, May 11–17, 2025, page 4.

Paltry Peace Prospects as the AA’s Power Grows

As argued by the International Institute of Strategic Studies, powerful ethnic armies like the AA are in a deteriorating security dilemma with the Myanmar military. Failing to hold peripheries like Rakhine, the military conducts airstrikes and imposes blockades to disrupt rebel governance. Unable to prevent either, the AA launched ally-supported forays into neighboring states and regions to retaliate and secure its borders.

China has attempted to mediate these tensions, but Beijing has fewer pressure options for the AA than for armed groups based near China’s borders. Although the AA and the Myanmar military reportedly met for talks in China in December 2024, no agreement was apparently reached. The AA has avoided overly antagonizing China by withholding a full-scale assault on northern Kyaukphyu Township, the site of oil and gas terminals, a deep seaport, and other Chinese infrastructure projects. However, clashes continued near these projects in April 2025.

Although the earthquake that struck Myanmar on March 28, 2025, prompted announcements of unilateral ceasefires from the AA and the Myanmar military, the AA captured a military outpost a day after the announcement and the military has continued a brutal bombing campaign. This is unsurprising; in a February speech, Senior-General Min Aung Hlaing emphasized the growing threat of the AA and allied “terrorists” in Magway, Bago, and Ayeyarwady.

In Magway and Bago, the AA and its allies threaten most of the factories feeding the Myanmar military war machine. Although limited to the western edge of Ayeyarwady in April 2025, conflict between the AA and military could expand, threatening an estimated 30% of national rice production and further decreasing the number of townships where Min Aung Hlaing can hold his planned election. With increasing leverage, the AA has fewer reasons to engage in ceasefire negotiations.

Threats to Other Resistance Stakeholders

While the AA’s increasing leverage has put the junta on notice in western Myanmar, there are challenges for other resistance actors. Supporting other actors threatens the junta but has also enabled the AA to expand its influence in Chin State and in Bamar-majority areas that are considered the NUG’s home turf. This has exacerbated splits within the Chin resistance while potentially pulling resistance groups from the NUG’s orbit, further fracturing an already divided resistance movement and decreasing the NUG’s long-term viability as the default alternative to the military government.

Disagreements over post-coup governance undergirded by geographic and tribal differences solidified into two rival Chin resistance coalitions in late 2023: the Chinland Council and Chin Brotherhood. Although agreeing to merge as the Chin National Council in February 2025, they have yet to write a governing constitution, indicating full reconciliation will not be an immediate process. The Chinland Council is led by the oldest armed group in the state, the Chin National Army (CNA), which has been alarmed by AA support for the Chin Brotherhood. A CNA leader claimed “[t]he AA’s hidden political agenda is to create a greater Arakan State” and implied the Chin Brotherhood was helping this effort.

The CNA has been one of the NUG’s few official EAO allies, so AA activities in Chin could be a further stumbling block to cooperation with the NUG. The NUG has attempted to attract the AA to its umbrella, for example, by diluting a statement about alleged AA atrocities against the Rohingya in May 2024. However, NUG efforts have likely been constrained by the perception it is dominated by National League for Democracy members who supported the military’s anti-AA campaigns pre-coup. Further, the NLD had refused to engage with Rakhine nationalist parties when it unilaterally selected the state’s chief minister. Indicating strained relations at present, the NUG was not among about 30 groups that sent letters congratulating the AA on the 16th anniversary of its founding.

People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) under the NUG might opt for more closely following the AA because of the NUG’s challenges in funding, arming, and strategizing to suit smaller groups’ local conditions. Well-armed and geographically closer to smaller groups, the AA is likely eager to support localized movements rather than deal with the NUG and its national leadership aspirations.

Offering an attractive alternative to consolidated power under the NUG in Myanmar, the AA has attracted sympathetic groups like the Generation Z Youth Army (GZA) and the Burma National Revolutionary Army (BNRA), which have bad blood with the NUG: an NUG-aligned PDF detained several members of the GZA in 2023, and BNRA leader Bo Nagar frequently accuses the NUG of trying to undermine his group. The GZA and BNRA fought alongside the AA in the capture of Mindat, and the GZA fought under the AA in Rakhine in February 2024. Contrasting the AA’s success in countering the junta with the NUG’s own challenges, other sympathetic groups may find the AA a more attractive and effective alternative for countering the junta, further complicating a resolution to Myanmar’s civil war.

Conclusion

The AA is expanding its influence across southwestern Myanmar through an axis of post-coup resistance groups, broadening its alliance network across the country. The AA has long had a presence in northern, northeastern, and southeastern Myanmar, giving it multiple theaters in which to fight against the Myanmar military and shape national politics. Now, in the southwest, the AA will unequivocally be the senior patron with proteges to direct for its cause, and in the Bamar-majority heartland, no less.

The AA’s sphere of influence is not just prying the southwest away from the military orbit; it is also reordering resistance power politics altogether. The AA’s successes and increasing support from smaller actors demonstrate that the group is establishing a sphere of influence beyond Rakhine that threatens the junta and rivals the NUG.

Some observers believe the AA faces a dilemma of expanding beyond Rakhine State or seize towns like Sittwe and Kyaukphyu. Instead, the AA may consider the two towns more useful outside of their control. As long as they threaten the capital, Sittwe, and the center of Chinese projects, Kyaukphyu, the Myanmar military must divert resources away from more active fronts in Bago, Magway, and Ayeyarwady to avoid losing these critical sites in Rakhine.

The AA will likely continue to invest most heavily in Ayeyarwady. The Rakhine Yoma’s forbidding peaks fortify AA borders with Magway and Bago, but the Yoma slopes into more traversable foothills on the Ayeyarwady border, making this area the most likely route for a Myanmar military counteroffensive. Moreover, the Pathein-headquartered Southwestern RMC is just 40 miles from the border. To cut off the base from the north, the AA has staged a four-pronged attack roughly along the Pathein-Monywa road in Ayeyarwady. Next, they may seek to blockade the road connecting the RMC to the Hainggyikyun naval base to the south and disrupt lines of communication to the east. Just as local allies have been force-multipliers in other theaters, resistance groups in Ayeyarwady and allies will be key for navigating the terrain, justifying the group’s incursion as a liberation rather than an invasion, and attracting local recruits. The AA’s ability to leverage groups in this manner will continue to bolster its offensives, continuing to challenge the junta in western Myanmar in the coming months.

Drake Avila is an independent analyst who studies conflict dynamics in Myanmar and was previously a daily news briefing writer for Frontier Myanmar.