The ongoing tensions in Nineveh’s municipal council highlight how regional powers vie for influence in Iraq’s local elections.

Uncertainty and poor governance have fostered an environment of competition for power and leverage within Iraq, both between the Kurdish regional Government (KRG) and Government of Iraq (GoI) and between Turkey and Iran. These dynamics are generating new points of friction and hostility, particularly at the municipal level. Last December’s long-delayed Provincial Council elections in Iraq have opened a new chapter of political contestation between local actors and regional rival countries. Internal fragility within the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)—particularly between the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)—has spilled over into Iraq’s Disputed Internal Boundaries (DIBs), claimed by both the KRG and the GoI. Subsequent disputes within the elected municipal councils to agree on governor positions in Iraq’s DIBs have further highlighted these tensions.

Politicking in the Nineveh Provincial Council

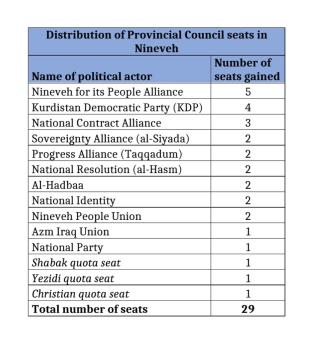

The Nineveh province, including the Sinjar district, is one such contested governorate and one of the most strategically significant regions for both Iran and Turkey. The Nineveh Provincial Council consists of 26 seats, plus three minority quota seats—one each for Christians, Yezidis, and Shabaks (see Table). Post-election negotiations resulted in the formation of two main political alliances: The Nineveh People Union Alliance, holding sixteen seats, and the United Nineveh Coalition, holding nine seats. This division aligned the Provincial Council between Iranian and Turkish allies respectively. While the structures of The Nineveh People Union Alliance are connected to the ruling alliance of Coordination Framework in Baghdad and actors such as Rayan al-Kildani (general secretary of the Babylon Movement) or Falih al-Fayyadh (chairman of Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF, known as al-Hashd al-Sha’bi)), the United Nineveh Coalition is composed of various Sunni groups and individuals such as Abdullah al-Nujaifi (son of Atheel al-Nujaifi, the former governor of Nineveh).

The framework of relations between both coalitions can be framed as occasional cooperation or competition over the issues connected to local administration. The Nineveh People Union Alliance —including the PUK, which has historically been backed by Iran—pushed for changes to twenty key administrative positions in the Nineveh province, including the replacement of seven district mayors and thirteen sub-district mayors. In response, the United Nineveh Coalition and the KDP boycotted the process, suspended their membership in the Provincial Council, and called for the dismissal of the Council’s Presidency.

A key element of this dispute is the appointment of Dawood al-Jundi, the PUK representative for Sinjar, as Sinjar’s new district mayor. This move was boycotted by PMF chairman Falih al-Fayyadh, who claimed Jundi was too closely aligned with Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (AAH), and eventually led the Provincial Council to appoint Saido Khairi as district mayor instead. Yet despite the boycott, Sinjar’s Sinuni subdistrict fell under PUK control, legitimizing Iran’s presence in the region through a recognized Iraqi political party, especially since the Iraqi government outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)-affiliated political parties in July of this year. This development highlights Iran’s growing influence in Nineveh, where it relies on allies like the PUK, PKK, and various PMF elements dominating Sinjar and its surrounding areas.

Additionally, the KDP filed a complaint with the Iraqi Federal Court in protest of the appointments during the Council session its coalition had boycotted, positioning itself as the opposition to the Nineveh Provincial Council. However, on October 10, 2024, KDP and Sunni Arab Alliance ended their boycott of the Nineveh Provincial Council meetings. While the United Nineveh Coalition qualified this decision by emphasizing that it will only attend Council meetings that are related to the provision of services in the province, the withdrawal of this complaint signaled that KDP still wishes to be included within the Council (and to be included within the decision-making processes on the local level). Moreover, this move could be seen as KDP’s willingness to normalize its relations with Iran and the GoI. Meanwhile, its limited participation may be intended to demonstrate disagreement with other local political actors and the policies they implement in the province.

Iranian Successes at a Local Level

The outcome of these elections emphasizes the ongoing success of Iran’s localized strategy in Iraq. Since 2003, Iran has developed a dominant position over the Shia-majority GoI through various Shia political parties while cultivating the loyalty of several brigades within the PMF at the local level. Iran has specifically worked to co-opt ethno-religious minorities such as Shia Shabaks, Shia Arabs, Shia Turkmen, Sunnis, Christians, and even Sunni groups like the 56th Brigade PMF in Hawija. The results of the December 2023 Iraqi provincial elections further solidified Iran’s political leverage, building on its reach via the array of Iran-linked paramilitary groups operating in Iraq. Through this strategy, Tehran is securing the logistics route between Iran and Lebanon, which is particularly significant given the ongoing Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon aimed at countering Hezbollah.

Iran’s long-standing local and regional presence has significantly strengthened its foothold over time while gradually diminishing Turkey’s influence, especially in the provinces of Kirkuk and Nineveh (additionally, Tehran is increasing its role within in the Diyala province). Besides its support for well-known national organizations such as the Badr Organization, AAH, and Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH), Iran also supports various local and regional allies in the disputed territories: including the PUK, the Babylon Movement, and local elements of the PMF, such as the Quwat Sahl al-Nineveh (Brigade 30), Kata’ib Babiliyoun (Brigade 50), the 16th and 52nd Turkmen brigades, and various brigades in Sinjar. Consequently, the influence of Turkey’s allies—such as the KDP, the Iraqi Turkmen Front (ITF), and Sunni political figures like Khamis al-Khanjar—has diminished.

The narrative of protecting territory from the resurgence of Sunni jihadism—such as Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and later the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS)—helps to legitimize Iran’s position. Its inclusive approach allows a variety of actors, even those with differing backgrounds and ideologies, to join their front. For instance, some groups within the PMF may not be staunchly pro-Shia, but they align with the PMF because they view Turkey and extremist Sunni forces as threats, especially in the Nineveh province where ISIS attacks were commonplace. This inclusivity was symbolically highlighted when Iran’s new president, Masoud Pezeshkian, spoke Kurdish during an unprecedented visit to the KRI on September 12, 2024. A key characteristic of Iran’s strategy is that it does not act aggressively; rather, it ensures its presence is felt without an obvious overt domination.

Specifically, Iran’s growing influence is limiting the KDP’s ability to respond, prompting instead a normalization of its relations with Tehran. This shift became apparent in May 2024, when KRG President Nechirvan Barzani visited Tehran. The KDP’s geopolitical strategy appears to be shaped by the relatively passive stance of the United States and Turkey toward the Barzani family and its political party. This change in the KDP’s course was further confirmed by the aforementioned visit of Pezeshkian.

Turkey’s Strategic Losses

Turkey’s long-term strategy is to increase its influence in these same areas of Iraq by positioning itself as the sponsor and advocate of the Iraqi Turkmen minority, a Turkish-speaking ethnic group primarily living in Iraq’s DIBs. This narrative plays a significant role in Turkey’s political messaging directed at Iraq. In addition to Ankara’s efforts to curb Iranian influence, the latter’s growing provincial presence is a concern for Washington policymakers, particularly as it relates to broader U.S.-Iran competition. With the planned reduction of U.S. troop presence in Iraq between late 2025 and into 2026, Iran seems poised to gain even more ground.

Thus, a loss of influence in Nineveh is a blow to Turkey’s overall strategy in Iraq, since one of its main objectives in Iraq (and Syria) is to counter the PKK, whose logistical network extends from the Qandil Mountains through Sulaymaniyah province, Makhmour, Sinjar, and into the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). In its efforts to limit PKK influence, Turkey has expanded its presence in KDP-controlled areas of the KRI, including Gara, Metina Mountain, Haftanin, Avashin, Basyan, Sine, and Hakurk. Likewise, Turkey views PKK-PUK ties as a threat to its national security: recent drone strikes in the Sulaymaniyah province—the fount of the PUK’s political heritage—have been widely attributed to Ankara.

Turkey’s efforts have likewise played out in neighboring Kirkuk, where it seeks to exert control over the local security situation by supporting Sunni Turkmen through the ITF. Despite the ITF securing only two seats in the Kirkuk Provincial Council, Turkey has advocated for a Turkmen to assume the role of Kirkuk governor, arguing that the city has had Kurdish and Arab governors in the past, but never a Turkmen one. However, Ankara strategy to keep its influence through Turkmen and Sunnis failed due to intra-division of these ethno-religious groups, the alignment of some of them with Iran and their poor election results in general.

Turkey’s actions are overt; it maintains a military presence in Iraq and actively combats groups it considers enemies. Until late 2023, Turkey wielded significant influence in Nineveh’s local government through its Bashiqa base. However, following the 2023 provincial elections, pro-Iranian political forces gained a stronghold in the area, reducing Turkey’s influence. The formation of new local governments in Nineveh and other disputed territories means that these bodies are now less aligned with Turkish interests.

The outcomes in Nineveh reflect how the KDP—and therefore Turkey—is gradually losing influence in both Sinjar and the broader Nineveh province despite Ankara’s increased military presence in the north of Iraq, including Ankara’s new security agreement with Baghdad signed in August 2024. Previously, Turkey held considerable sway in the region, but the outcome of Nineveh and other provincial elections along the DIB suggest it is experiencing a sharp decline in leverage. While the stated goal is cooperation against PKK activities, Turkey also seeks assurances that its control over Bashiqa will remain intact, undisturbed by Iran’s growing presence in Iraq’s disputed territories. Ultimately, Turkey may be attempting to compensate for its declining influence on the ground by relying more on its local allies and its new bilateral agreement with the Iraqi government.

Regardless of the outcome, the involvement of regional and neighboring countries in Iraq’s internal affairs does not address the country’s underlying problems, nor does it provide a peaceful solution. These regional powers’ support for groups aligned with their respective agendas helps drive internal friction within Iraqi politics, and both use claims of public opinion to justify military intervention as a means of resolving issues. Both Ankara and Tehran are leveraging their local allies (or proxies) to implement their regional strategies on the ground.